A Brief

History of Energy in Tanzania

The road from

a colonial to post-colonial energy system

The first public

electricity supply in Tanzania was established by the German colonialists in

1908 (by then Tanganyika) and served the railway workshops and towns where the

colonialists were mostly staying (Edward

and Hard, 2019). During colonial eras, electricity lines were installed

directed to productive areas such as industries owned by colonial powers

(Chaplin et al., 2017). In rare cases electricity was installed

to improve livelihoods and ensure social services of community households. The

role of electricity in promoting productivity at household levels remained

limited and thus impaired contribution of economic growth from household

livelihood activities. It is under this circumstance many of households in

Tanzania remained with no access to electricity. However, after independence in 1961 the first government of Tanganyika came

up with an intention to develop the national electricity generation for

domestic, industrial use and to promote irrigation of rural agricultural land.

Potential foreign partners and engineers were invited and were given an

opportunity to support. However, in the process they changed the main focus to

concentrate on hydropower alone and agriculture was not given priority.

Consequently, the British dominance in the power sector was replaced by others

such as Swedish and earlier knowledge produced by British colonial officers was

disregarded. Discounting previous knowledge had its implications on future

energy sector development.

The birth of TANESCO

Empower communities by

access to energy

In 1964, the Tanzania

Electric Supply Company (TANESCO) was formed as a public power utility. Electricity

was seen as an essential element for improving livelihoods in rural areas and

hence limit both rural-urban migration and deforestation (Chaplin et al., 2017)

which were at an alarming rate. TANESCO was tasked to undertake studies and

start planning new power projects to meet the increasing industrial,

commercial, and rural township power supply demands. It was during this time;

large-scale hydroelectric plants were built and subsidized by the government to

reduce costs from imported fossil fuel (Cook et al. 2015).

A bumpy road toward energy for everyone

The

challenges of transforming an industry-focused colonial energy system

However,

it does not need to be emphasised that the process to increase electricity

access in rural areas of Tanzania, remained focused on areas which were considered

productive, towns and for decades has ignored rural areas. This shows how the

colonial system in the energy sector continued to influence energy provisions

in the country. Projects that intended to electrify rural areas were supported

by donors or had slow advancement. Still in rural areas electricity was neither

used to increase productivity nor serve the cooking and heating sectors. Even

in some rural areas where households had access to electricity, it was only

used for lighting (Bernard, 2012). Rural electrification did not increase a

number of households with connections due to high prices and did not reduce

reliance on wood (Bernard, 2012. Chaplin et al., 2017). Deforestation rates linked to unsustainable use of biomass

was thought to increase and rural-urban migration did not slow down. In

the period of 1980s and early 1990s, Tanzania switched to structural adjustment

policies where government and donor-funding rural electrification projects were

significantly reduced. It was learnt that large-scale projects to expand grid to

rural areas were expensive and increased debts to the state-owned utility

company (Bernard, 2012).

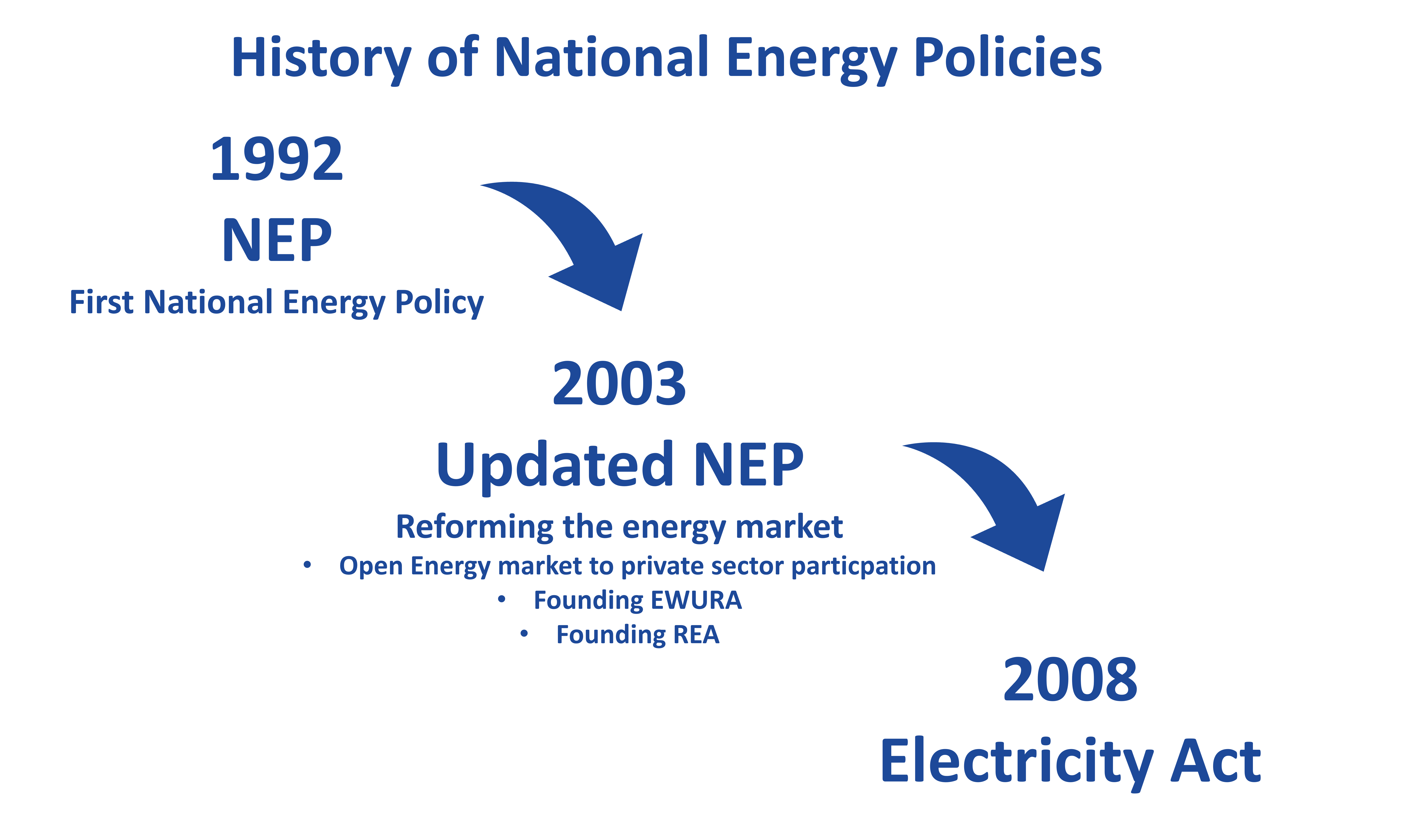

The History of National Energy Policies

Promote productive use of energy

In general, all efforts

failed to increase access and promote productive use of energy in rural areas and

particularly at household levels, this is considered to

be one of the reasons for existing poverty (CANTZ, 20219; Garcia et al.,

2017). In 1992, the government formulated the first National Energy Policy

(NEP) as a response to socio-economic reforms which happened in 1990s (URT;

2015). In the early 2000s, NEP was re-formulated and launched in 2003 with an

intention of reforming the energy market and attracting private sector

participation in the Sector (URT, 2015). It was through the implementation of NEP,

2003; Energy and Water Utilities Regulatory Authority (EWURA) was established;

Rural Energy Agency (REA) and

Rural Energy Fund (REF) became operational. Both Small Power Purchase

Agreements (SPPA) and the Electricity Act 2008 were formulated.

Energy for Development

A key to fight poverty

Since the 1990s, energy

has been explained as one of the important socio-economic transformation

enablers. It

has since been considered both in the Millennium Development Goals and

Sustainable Development Goals as an important instrument to fight poverty and

hunger, enhancing education, health, transport, empowering women, ensuring

access to water and decent jobs. The utilisation and promotion of renewable

energy and energy efficiency are among the SDGs and well linked to the Paris climate

agreement. Renewable energy and energy efficiency are also considered to be

important in addressing energy poverty and building resilience to rural and off

grid communities. Decentralised energy and especially utilising local renewable

energy sources are now widely accepted to ensure sustainable development. Despite

their emphasis documentation in many national plans and agenda, their

implementation has been lagging significantly. The current legislations in the

energy sector have less emphasis on amplifying the role of renewable energy and

decentralising energy compared to grid extension. If the abundant renewable

energy sources are not utilized the current plans may not meet present and

emerging energy demands and sector challenges.

(This section is part of the Policy Recommendation Report that analysis the landscape of the Energy Sector and Policy in Tanzania. Learn more about it here: https://cantz.or.tz/publications/20 )